If you grow roses in BC’s lower mainland, overall you’re pretty fortunate in your climate. Maybe not quite so fortunate as a rose grower in the highlands of Ecuador, but definitely lucky in comparison to a rose grower in Flin Flon, Manitoba. We benefit from a mild maritime climate, four (usually) distinct seasons, and we’re far enough north that our spring and summer days are extended – extra time to enjoy our gardens when they’re at their best! Take that, Ecuador!

As mild a climate as we Lower Mainlanders usually enjoy, we need to be aware of the occasional arctic outflow wind. These weather events are the most dangerous time of year for roses in your garden. Here’s a meteorological definition. If you work outdoors in the winter weather, you’ll notice when the wind begins coming in the wrong direction, from the east instead of the west or south. There’s a particular chill to that wind that will tell you something ugly is on the way.

Some of these arctic outflow storms can be vicious, in a relative way, of course. We’re accustomed to gentler weather conditions here. Maybe someone from Edmonton would scoff at this kind of storm, although I dare say that at the worst of times, when the arctic wind is whipping snow and ice sideways across the Matsqui and Sumas flats, even our brave Edmontonian would rather be inside.

They may happen only a few times a year, there are a few problems these arctic outflow events pose for our roses.

- They can come unexpectedly, any time in the winter or even late fall, before our garden plants have really decided to take winter seriously. If your roses haven’t “hardened off” for the cold season, they’re more susceptible to damage.

- Low humidity. Cold air holds less moisture than warm air, and wind sucks moisture out of plant tissues faster than still air. The result is that rose canes, especially younger longer shoots, will become dessicated by the wind. This is what causes those blackened shoots when the spring comes.

- In addition to sucking moisture faster, the winds also mean that any snow cover that would have been moderating the soil temperature is probably blowing right past the neighbor’s house. Times like this, a little bit of tree cover as a wind break is much appreciated.

I mentioned that roses need to “harden off” if they’re to avoid winter damage. For roses grown outdoors, you don’t have much control over this, except that you probably chose the roses in the first place, and some do a better job of it than others. I went out to the garden today (Nov 20, 2012) to see how the roses are doing. We’ve had a mild fall, and as expected, there are a few roses that are pushing it a bit, still putting up succulent new growth rather than going dormant.

In many roses, bright red stems and leaves mean new growth. ‘Anisley Dickson’ here is also throwing several new flower buds. It’s a bit of an issue with the repeat blooming genes that breeders select for… the rose will continue to put on new growth to support flowering, even when those flowers are unlikely to finish. For roses that don’t know when to quit blooming, an outflow wind can be devastating. The only control you have is to choose your roses varieties carefully.

In many roses, bright red stems and leaves mean new growth. ‘Anisley Dickson’ here is also throwing several new flower buds. It’s a bit of an issue with the repeat blooming genes that breeders select for… the rose will continue to put on new growth to support flowering, even when those flowers are unlikely to finish. For roses that don’t know when to quit blooming, an outflow wind can be devastating. The only control you have is to choose your roses varieties carefully.

‘Veilchenblau’ is a tough rambler rose. Even if it takes some damage through winter, it’ll put on a good show next year. In this picture, you can almost feel how soft this wood is. This is an example of a rose that’s so vigorous, it can go ahead and risk continued growth because it’s strong enough to thrive even if winter knocks it on its butt. What I’d rather see:

‘Veilchenblau’ is a tough rambler rose. Even if it takes some damage through winter, it’ll put on a good show next year. In this picture, you can almost feel how soft this wood is. This is an example of a rose that’s so vigorous, it can go ahead and risk continued growth because it’s strong enough to thrive even if winter knocks it on its butt. What I’d rather see:

This is ‘Emily Grey’, a whichuraiana climber. This rose is in an exposed position along the back fence of our farm, and it looks like it takes the threat of winter seriously. Remember I wrote earlier that the color red in rose stems can indicate new, soft growth. That’s not the case here – this rose variety has wood that matures to this handsome mahogany color. Notice the buds are tight at each node, and ‘Emily Grey’ has even dropped it’s leaves.

This is ‘Emily Grey’, a whichuraiana climber. This rose is in an exposed position along the back fence of our farm, and it looks like it takes the threat of winter seriously. Remember I wrote earlier that the color red in rose stems can indicate new, soft growth. That’s not the case here – this rose variety has wood that matures to this handsome mahogany color. Notice the buds are tight at each node, and ‘Emily Grey’ has even dropped it’s leaves.

Not all roses will drop leaves before the winter. Here’s one that has fully hardened, but is still holding onto its foliage:

You’ll have to take my word on it that the stem this specimen of ‘Complicata’ is completely hardened off. I show this to emphasize that the leaves don’t need to drop for a rose to be ready. The firmness (maturity) of the wood is what counts. Don’t be tempted to strip the leaves from your roses. It’s not only unnecessary, but probably does more harm than good by depriving the rose of the chance to finish the season in an orderly manner. When the leaves drop naturally, the attachment point is protected. Human hands pulling off leaves may cause injury, and give disease organisms a nice opportunity to get in.

You’ll have to take my word on it that the stem this specimen of ‘Complicata’ is completely hardened off. I show this to emphasize that the leaves don’t need to drop for a rose to be ready. The firmness (maturity) of the wood is what counts. Don’t be tempted to strip the leaves from your roses. It’s not only unnecessary, but probably does more harm than good by depriving the rose of the chance to finish the season in an orderly manner. When the leaves drop naturally, the attachment point is protected. Human hands pulling off leaves may cause injury, and give disease organisms a nice opportunity to get in.

So what do you have control over?

- Your choice of roses. Hybrid teas are some of the tenderest varieties, and many gardeners in the rest of Canada don’t even attempt them. Look up the rose’s profile on helpmefind.com and look for the climate zone of hardiness. Most of the lower mainland is comfortably in zone 7 or 8, but you may want to choose a rose that’s good to zone 5 or 6 if you have an exposed site.

- Location within the garden. You’ll have trees, shrubs, fences, hedges and buildings to take into account when you choose a spot for your roses. Remember that the worst of the outflow winds will be coming from the east, so place your tenderest roses to the west of something that can dampen the wind. I haven’t mentioned a whole lot about moisture in this posting, but if you’re choosing a site for a rose anyhow, be mindful of where there’s decent drainage. Even a hardy rose won’t stand a chance if it’s sitting in a puddle all winter.

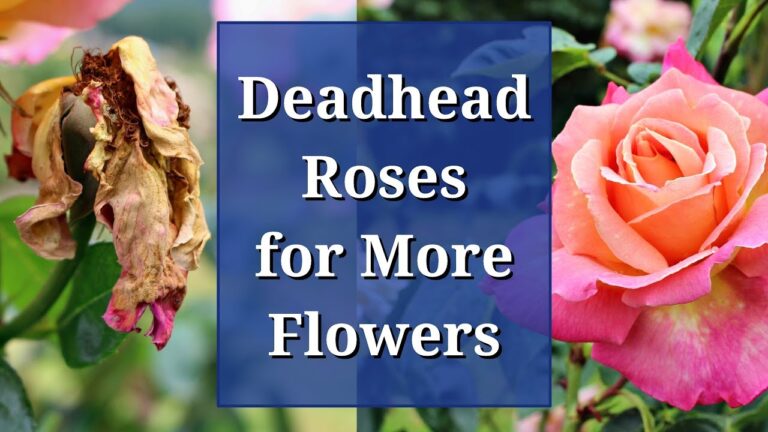

- Pruning and fertilizing. I tend to do most of my rose pruning in the early spring, when I can take out any canes that have been damaged by the winter. I keep on pruning most of the summer, shaping and tidying whenever I’m walking by a rose and have the pruners in my hand. Somewhere around August I ease off. It’s best to give this year’s growth some time to harden off. If you cut back too hard late in the season, the rose will likely respond by sending up more soft shoots. Likewise with fertilizer. A well-fed rose wants to grow and bloom, so I cut off the food supply in august as well.

- Mulching. I put a 3 or 4 inch layer of oak leaves ( I just happen to have a fairly large oak tree on the driveway) at the base of my roses. It moderates the soil temperature. In the spring it can be chopped and worked into the soil to add organic matter. Most any loose mulch will do. I’ve seen recommendations for tender roses to build a wire mesh cage around the entire plant and cover with a foot of mulch. It might work, too, but my initial thought is that if you need to go this far, you’ve chosen the wrong rose.

- Protect your containerized roses. It’s just a matter of choosing the best location you have available, and making it work. My cold frame greenhouse works pretty well, but not everyone has a greenhouse. A friend of mine (who has many more roses than I do) overwinters his container and tree roses in his garage, and it works beautifully. Do you have a back deck with some shelter from the wind? Can you collect them together under an outdoor stairway, or in the corner of the yard where they’ll get protection from the hedge on two sides? If you keep them outside where there will be wind, keep them bunched together so that they’ll provide some protection for each other. If you do find an indoor/greenhouse space, just be cautious about watering. Wait until the pot is relatively light and dry before watering fully. They’re not going through much water when they’re (semi) dormant, so don’t drown them.

All right. We’ve done what we can. Fingers crossed everyone?

Don’t stress. Roses are a lot tougher than they look.