Good advice on rose pruning should really begin with a question: why? Why should you bother cutting at all? What would happen if you didn’t prune your roses?

- The shrub might get taller than you’d like. You want blooms at a height where you’ll enjoy them

- Left to their own training, they may take on an unattractive or uneven shape. They can also invade the space of another plant or intrude on a pathway

- Dead, damaged, diseased & crossing stems will persist on the shrub, doing no one any good

- The shrub may become a bit congested with older stems, preventing proper air movement and sunlight from reaching the center of the shrub

By the way, these are the very same reasons you’d consider pruning any tree or shrub:

Size. Shape. Health. Thinning.

And when you prune for those 4 reasons, you’ll often spur on vigorous new basal growth for stronger stems and flowering.

If your rose is younger, and still needs time to establish – skip it. Likewise, if your established rose is a pleasing size/shape, and overall healthy you can get away with minimal pruning. I usually pick an older stem or two from the base for removal anyway, just to encourage fresh growth, but it’s totally optional. I want to include a video here that shows how I tackle this in real life – first with a rough cut for size and shape, then with the finer work down low on the shrub to thin and remove old and damaged stems:

I could just about end the article right here, but I won’t. There will be questions about when and how, and I don’t mind answering them in full, but I don’t want to give you the impression that it’s a complicated matter. You could pretty much tackle your rose pruning when it’s convenient for you and use a wide range of methods (including a hedge trimmer!) and so long as you’re making progress towards one or more of the above goals, it’s all good.

Irritatingly, some of the specific instructions about rose pruning you’ll have heard passed around as garden folk wisdom is fixated on what I view as irrelevant and maybe even unhelpful: the cutting angle, the position of the cut in relation to the next outward-facing bud, sealing the pruning cuts. As a side-note, this video where I made commentary on these “rules” for pruning roses more or less launched my YouTube channel:

I’ll quickly summarize and review these supposedly rose-specific rules here and also give you my assessment of whether the rule is worthwhile:

1 – Prune when the forsythia is in bloom (late winter): Somewhat agree. It’s a pretty good time to target because you’ll be able to take out any noticeable cold damage in the same step. That said, you can prune later in the season – even after flowering, and that works well too.

2 – Begin with dead, diseased, damaged or crossing stems: Mostly agree. It’s one of the main pruning goals I identified at the top the article. It’s also some of the most productive pruning – you can do a lot of good without any hard decisions. Whether you tackle this before or after shaping/reducing size is your call. In my actual work flow I generally take off some of the extra height and mass first so that I can get a clear look inside the shrub for these finer cuts.

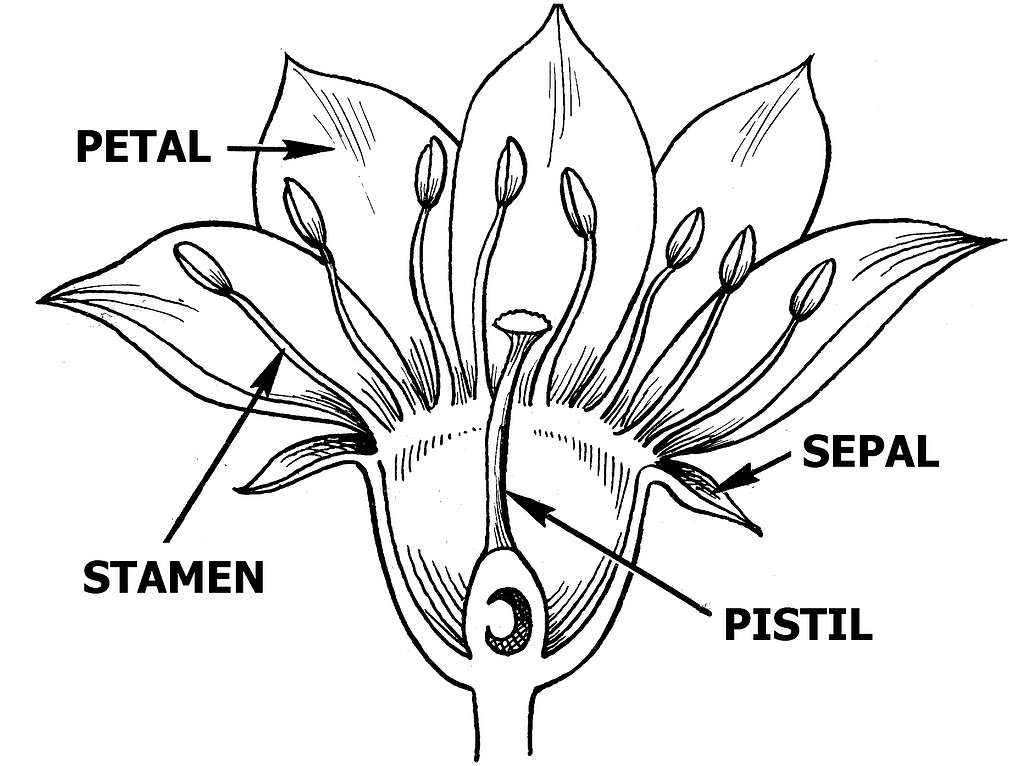

3 – Prune to an outward-facing bud: Mostly disagree. This advice goes on the mistaken assumption that your rose will only shoot from the bud just below your cut, and that choosing an outward-facing bud will promote a more open shape after pruning. In practice, your rose will likely shoot from multiple buds below the cut, and will fill in with stems and foliage wherever there’s sunlight available to fuel the growth. Choosing a bud to be outward is unnecessarily fussy in my view, and this advice just serves to confuse new rose growers.

4 – Prune low and to just a few stems: I somewhat disagree with any one-size-fits-all guidelines around number of stems and standard height after pruning. I suppose it’s meant to reassure new growers that if they follow the recommended height for a hybrid tea or floribunda, that they won’t mess it up. The pruning height and shape shown in the video (open, and down to 18 inches) is pretty typical of the advice given. It’s probably fine for a healthy, vigorous shrub rose like a Knock Out. Many of my roses would resent such a severe cut, and I know many gardeners who prefer a larger shrub in the garden.

5 – Use clean, sharp tools and disinfect between roses: Agree. This isn’t so much a rose-specific tip as just a generally good gardening technique. Cleaner cuts are less prone to die-back, and disinfected tools reduce the risk of spreading pathogens between plants.

6 – Cut on an angle and seal your cuts with glue: Mostly disagree. I couldn’t find anything before (or even since) the video to back up the notion that cutting on an angle is helpful, and what I did find in the research seems to indicate the opposite: the larger the surface area of the cut, the more it’s associated with poor outcomes.

This next bit gets me into hard feelings with some gardeners. If you think it’s worthwhile to seal your canes, I won’t stop you – and you can even skip to the next paragraph if you’re happy to keep doing so. Sealing the cut with glue (or nail polish or pruning sealer) isn’t something that’s likely to protect your roses from serious cane borer damage. The most damaging of cane borers on roses don’t enter through the cut stems, and they’re not flying around in the late winter (if that’s your timing) waiting for you to prune. Your best defense against the worst of the cane borers is careful observation during their active season (generally mid-spring to early summer) to quickly identify and remove infested stems.

Do I really mind you if cut on an angle or put nail polish on your cut stems? Of course not. You do you. My only point is that when these nitpicky practices are listed as the “right way” to prune roses, it adds complexity to an already intimidating task.

7 – Prune to a pleasing, balanced shape and a more open center. Yes. Let’s not overcomplicate the issue. A rose is just like any other shrub, and usually only needs a bit of thinning and shaping for best garden performance.

Common Questions

When I’m presenting this topic at pubic events (garden clubs, etc.) this is the point where the audience begins asking more specific questions. For convenience, I’ve answered most of these in video format at one point or another, so I’ll add those video and some commentary below.

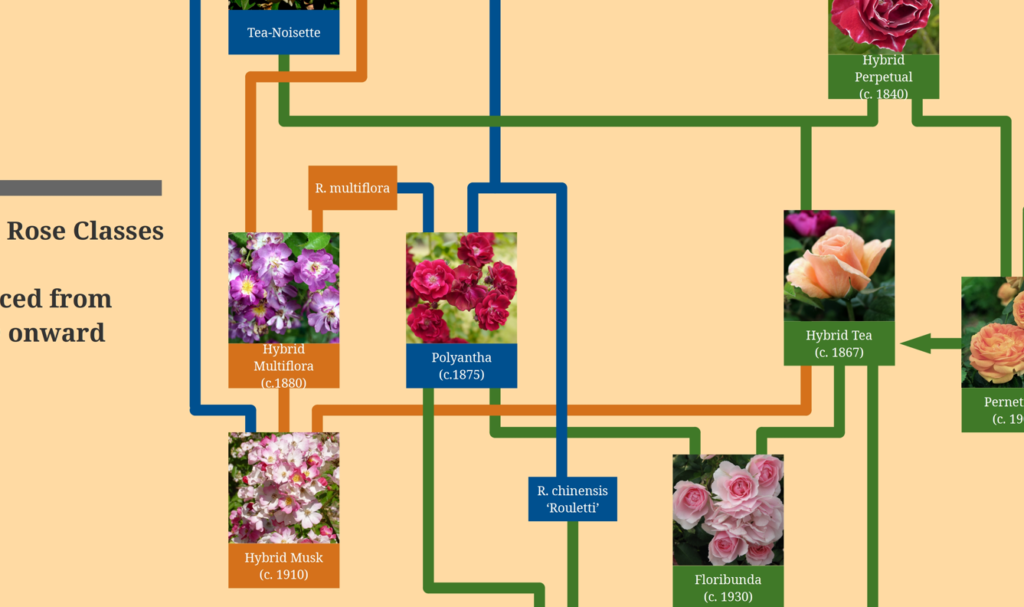

Timing: As mentioned above, you can get away with pruning your roses over a wide stretch of the season. It does bear saying that once-blooming roses (species and some old garden roses) depend on their established stems for flowering, so an ill-timed severe pruning will result in a much less impressive display. Here’s a video (and flowchart, for those inclined) to help you work through the best time for puning:

What about climbers? You’ll improve flowering by keeping some longer stems in place and trying to train those stems horizontally. I’ve made two videos with examples, but here’s the one where I talk about it more generally:

On a similar topic, some viewers look for a little guidance for dealing with standard or tree roses. They’re top-grafted, so care should be taken to avoid damaging the graft union at the center. Here’s my video:

Finally, I hear a lot of questions about roses that have been neglected, and over the years have become overgrown. If they’re overall healthy, they can accept quite a severe pruning to bring them back down to size. I’ll include one final example video here just to embolden you to take up the loppers:

A few final thoughts:

If you’re in a temperate climate and you’ve chosen to take on your pruning at the traditional time of year, late winter, it would also be a decent time to do a bit of clean up. You could remove any persistent old leaves that haven’t dropped. You can also remove dropped leaves from the base of the plant, so that they don’t carry over the foliar disease from one season to the next. A refreshing or replacement of the mulch would be helpful in this regard too. I personally make my first application of bulk organic amendments at this time – I use alfalfa pellets a lot, but I’d be just as satisfied to apply a shovel scoop of compost or manure.