“Spray” is not a four-letter-word. It’s just a method of application, equally useful for liquid kelp extract as for certain biological controls like nematodes or beneficial bacteria – but that’s not the kind of spraying we’re really talking about here, is it? The kind of sprays that quickly divide the opinions of neighbors and gardeners are the synthetic pesticides.

As a very quick aside, it’s often said that one should avoid the topics of politics, religion and money if you want to keep conversation polite in general company. When it comes to gardeners, avoid talk of invasive species, peat moss and pesticides. And while I agree that it’s a shame we can’t have reasonable conversations on topics that could really benefit from some reason, you’ll inevitably tweak someone’s strong feelings along some pretty predictable ideological fault lines and that’s no fun.

I’m going to carry through with this topic anyway, but in order to avoid (or at least delay) any hard feelings, I’m going to approach this from a place of common ground: no one, and I mean no one, wants to climb into a spray suit on a hot day, strap on tightly-fitted respirator, and walk around the garden with a backpack sprayer filled with pesticides.

It’s unpleasant, dangerous, expensive and usually only solves a pest problem for a short period of time, while also posing risks to the non-target organisms who might actually be the “good guys” and part of the solution. I never assume that gardeners are out there spraying just for fun but rather because they feel they’re out of better options. So it only makes sense for me to focus the first part of this article on those: the better options!

Resistant Varieties

I’d love to grow the thornless and beautifully fragrant Bourbon rose Zéphirine Drouhin. I’ve tried. Three times, in fact.

It’s just too susceptible to foliar disease in my climate that it proved difficult to grow well, regularly dropping most of its foliage to black spot, powder mildew or both.

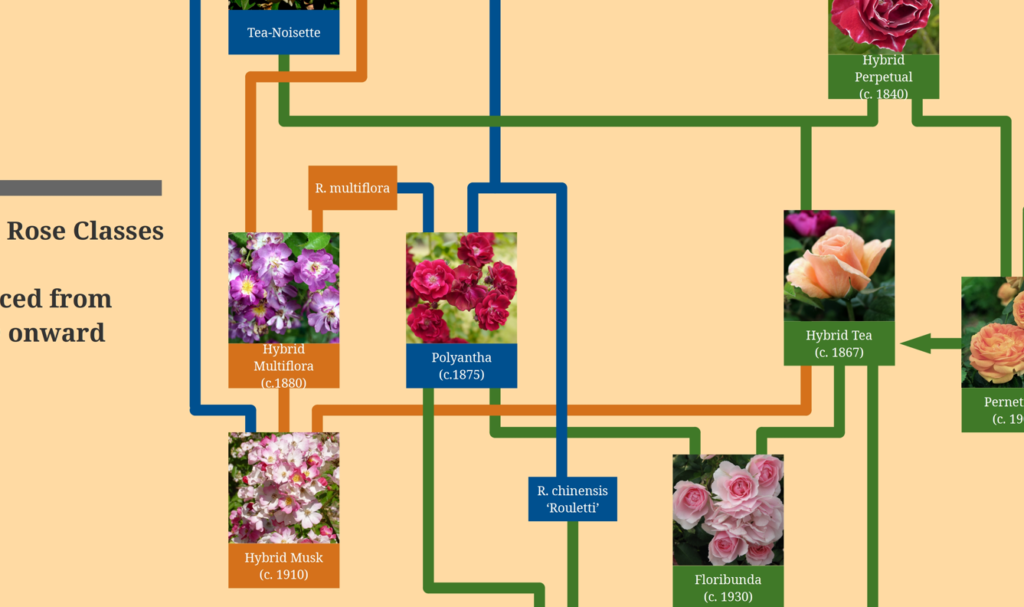

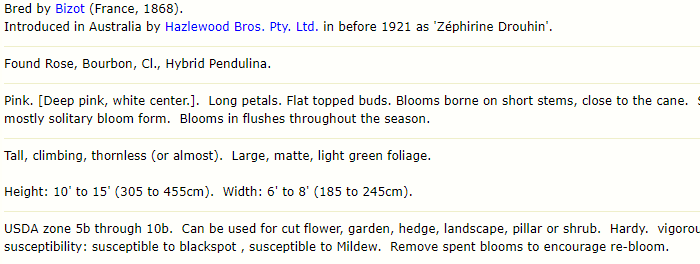

Once you know the challenges of you climate (and this is something experienced rose growers in your area are not reluctant to share) it can be helpful to guide your buying choices towards roses that are best suited – or at least not poorly suited – to resist those problems. I sometimes take for granted that rose gardeners are familiar with Helpmefind, a sort of “Wikipedia” or rose varieties. If I’d been paying attention to the write-up there, I might have skipped my efforts to grow Zephirine (at least the second or third time!)

There it is on that final line, in plain black and white. They usually post a rating for at least blackspot and mildew, but also include Member Rating for overall tolerance of disease, heat, cold, rain and shade. It bears saying here that you’ll have a lot fewer problems with pests and diseases if you’re rose is well suited to your climate and its location in the garden.

The Basics of Rose Care

It seems to follow from what I just wrote above that an rose coping poorly with extreme heat & humidity or too much shade is going to be more susceptible to pest problems. This is undoubtedly true. That old expression that says “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” is exactly the wrong approach when it comes to plant health. It should be reformulated as “What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker and more susceptible to secondary infection” – not as uplifting, I admit. In fact, the reason yellow sticky cards (for pest monitoring) are yellow is that the pests are especially attracted to the sickly yellow leaves of stressed plants.

Look after the basics: a reasonable soil with decent drainage and not too high a pH. A sunny spot – at least 6 hours for most roses, with some exceptions. Appropriate watering. A mulch to maintain consistent moisture and temperature. Fertilizer as needed – but not so much (especially nitrogen) as to spur on an excess of lush green growth, because the pests love that too!

Plant for Diversity

One reason traditional field agriculture is so reliant on spraying pesticide is because they plant in monocultures. A whole field of corn planted in close proximity can be quickly decimated when a fast-reproducing pest moves in. In mixed landscapes, there’s more balance between various predators, parasites and pests. I strongly encourage rose growers to plan and plant for diversity in the garden, which also creates a perfect excuse to source all the interesting shrubs, perennials and annuals you’ve ever fancied, even in passing.

For more on the biological approach to pest management, and some of my plant recommendations, here’s a video on the topic:

Sanitation and Pruning

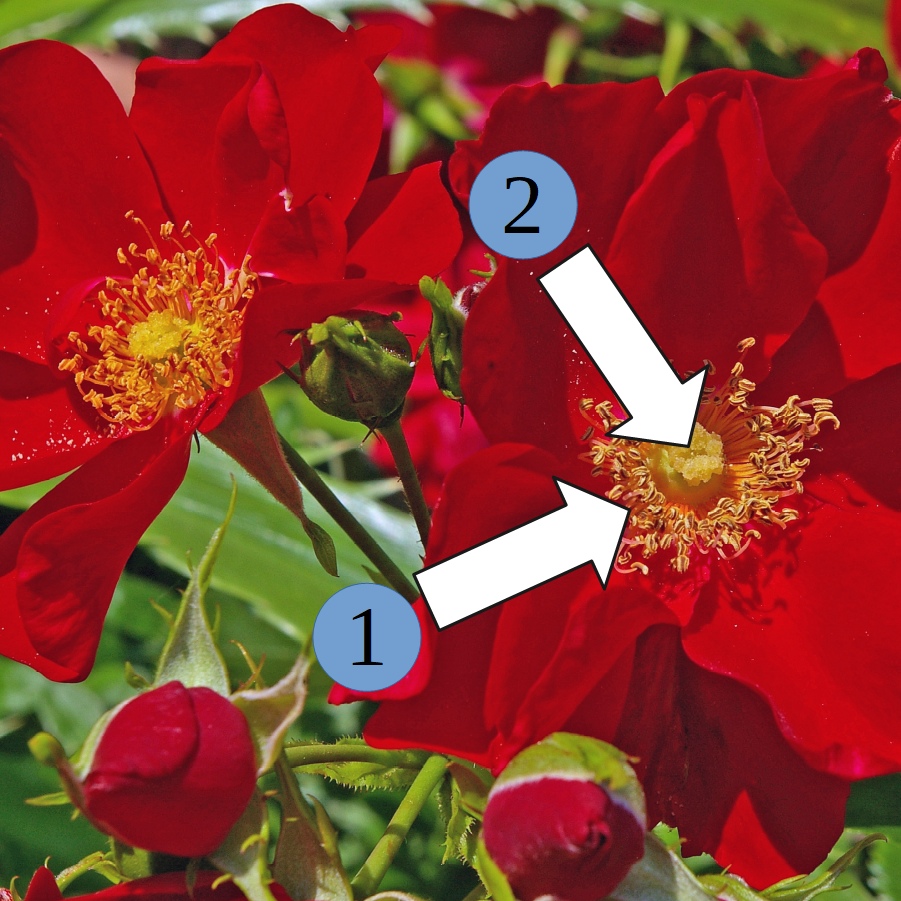

One cultural control to pests, especially foliar disease like blackspot and powder mildew, is to prune out any damaged, diseased and congested stems from low down and in the centers of the shrubs. Combine this with a stripping of the lower infected foliage as warranted by the severity of the outbreak. This kind of cleanup can reduce the chances of the disease spores reinfecting your plants, and also allows for proper air circulation within the shrub.

For a quick discussion on stripping leaves, here’s another of my video topics:

The classic time for a thinning pruning is just as your roses are waking up from winter (in temperate climates anyway). However, I tend to thin a bit throughout the season as I deadhead my roses. The earlier you catch signs of foliar disease the better I’ve found, but I really do focus my efforts on the most susceptible varieties in my garden.

Tolerance

It’s a dirty trick of rose culture that tells gardeners they should be looking for perfect blooms and spotless foliage. The same way that farmers have tried to educate produce customers that a crooked carrot tastes fine compared to a straight one, rose growers should let themselves off the hook for a bit of chewing damage on their leaves. One of the cornerstone principles of modern pest management is just keen observation and setting a “tolerance” level for pests and disease. This will come with time, as you see which warning signs of pests require intervention, and which require a shrug.

Biological Controls

My favorite biological controls are the ones that come for free! Birds and beetles eat slugs. Hoverflies eat aphids. Pirate bugs do a pretty good job on thrips. Predatory mites hunt down the spider mites. There isn’t an insect pest I can think of that doesn’t have its natural predators, and also, as noted above, plants that you can put in your garden to encourage them.

However, it may happen that an outbreak of pests overwhelms your plants faster than natural predators can deal with them. This is actually almost inevitable at certain points in the year. Pests reproduce very quickly when their food is plentiful(the roses, in this case are putting on fresh growth). The predators are naturally one step behind, as they need their food source (the pests) to build up before they can start their own population boom.

It’s nice to know that one of your options is to supplement with biological controls. Ladybugs are a well-known choice, but in my conversations with professional growers I’ve heard strong recommendations for generalist beneficials too. Your eventual choice will depend on the pest you’re dealing with and what’s available from local suppliers – who are generally pretty helpful with recommendations.

I should also mention that some biological controls are offered in ready-to-use products sold at garden and hardware stores. BTk is a bacteria used to control caterpillars, and it’s cousin BTi is pretty effective against fungus gnats in propagation (the product these come in is dunks or bits for mosquito control). There’s also Milky Spore to apply to lawns with Japanese Beetle larvae. So not everything needs to come from a specialty biological control company.

Natural or Organic Pesticides

Insecticidal soap is just true liquid soap (potassium salts of fatty acids) applied as a spray. It’s a contact pesticide, meaning it has to be sprayed directly onto the pest population to be effective. It’ll wipe out aphids with no problem, but has a little trouble with spider mites and thrips because they’ll shelter in their webbing or in the folds of flowers and distorted leaves. It will also kill non-target insects if they’re hit by the spray. There’s no residual action, so once the soap dries, the plant is safe again for pests and beneficials.

Sulfur is the purified straight-up element, applied either as a finely ground powder (usually suspended in water as a spray) or vaporized in a sulfur burner. It’s pretty effective against powdery mildew and spider mites. It shouldn’t be applied within 7 days of soap or oils

Horticultural oil is a refined paraffin or vegetable oil formulated to be less damaging to plant tissues while still offering some control of insects and fungal disease. See above that it shouldn’t be applied in close timing with sulfur. Like soap, it’s a contact pesticide for insects with no residual effects. It’s the product most recommended for scale insects.

Potassium bicarbonate is sort like baking soda (and sometimes used as a substitute) – but safer to use on plants. Sprayed in a solution (3% by weight) with water it’s broadly pretty effective for prevention (but not cure) of foliar disease. It’s even more effective when combined with chitosan (0.75% by weight) as described in this video:

I think it’s important to say that these more “natural” or organic type sprays aren’t guaranteed to be without harms. I like the above options because they have a long record of relatively safe use, because they’re targeted, don’t have residual effects, and because they’re shown not to result in pesticide resistance very readily. Those aren’t things you can say for the “hard” synthetic pesticides, but you should still treat any and all of these with due care. Understand the products, the risks and all safety precautions before applying.

Dormant Spray

Maybe my favorite kind of pesticide application is in the dormant season because it combines sanitation with prevention. Pest populations (both insect and microbial) are at their lowest and most inactive during the dormant season. Somewhat stronger solutions of lime-sulfur, dormant oil or copper-based sprays can be used to great effect in reducing their overwintering populations or spores before they can reestablish in the spring. I give details and answer questions about these sprays in the following vid:

The Hard Stuff…

In the same way as I acknowledge not all “natural” pesticides are intrinsically harmless, I have to say that not all synthetic chemicals are crated equally harmful. I personally have been able to draw the line (on my farm) at solutions offered above. Mainly I’ve focused on companion planting (to attract and support beneficials) and proper plant care, pruning and sanitation. I use the bicarbonate, soap, oil or sulfur in a very targeted way as needed during the active season, and only use dormant spray on susceptible varieties (if at all).

When I worked in a commercial wholesale nursery, they whole arsenal was available to us, and some of it was pretty scary. Organophosphates like diazinon and malathion gave me real concerns from a human health point of view – I wouldn’t use them then, and if you’re considering it, I’d just advise you to really understand all the risks.

Pyrethroids are related to natural compounds found in the Robinson’s Daisy (Tanacetum coccineum) – synthesized and reformulated to make them quite an effective insecticide with a short residual – usually a couple of days. I guess you could call that “natural-ish”. I mention it here because it’s been found fairly effective against rose midge, which as a pest doesn’t give you a lot of other options. Toxic to a wide range of insects, fish, reptiles, humans (at higher exposure levels) and especially to cats.

Spinosad might even be better included in the above (natural) category, as a chemical extract of a natural compound in a particular bacteria. Some certifying agencies permit its use in organic agriculture. It’s affective against a wide range of insects and hasn’t been found to be very dangerous to mammals. I mention it here because it’s often recommended against chili thrips, which are hard to tackle otherwise.