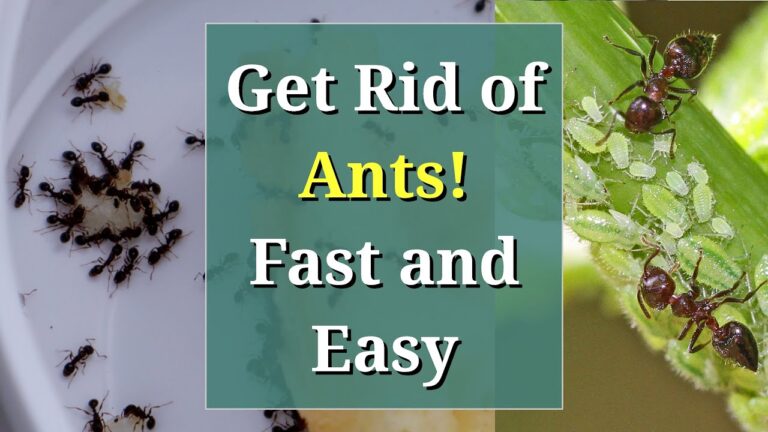

Aphid Control in the Garden: Effective Strategies for Managing Infestations

Aphids are a common and frustrating pest for gardeners, but with a better understanding of their behavior and the right management techniques, they can be effectively controlled. Jason from Fraser Valley Rose Farm brings his expertise to the topic, sharing practical strategies for addressing aphid outbreaks without resorting to harmful pesticides—or minimizing their use when…